Maimonides

Maimonides (March 30, 1135–December 13, 1204) was a Jewish rabbi, physician, and philosopher in Spain and Egypt during the Middle Ages. He was one of the various medieval Judaism|Jewish philosophers who also influenced the non-Jewish world. Although his copious works on Jewish law and ethics were initially met with opposition during his lifetime, he was posthumously acknowledged to be one of the foremost rabbinical posek|arbiters and philosophers in Jewish history. Today, his works and his views are considered a cornerstone of Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jewish thought and study.

Maimonides' full name was Moshe ben Maimon (Hebrew: משה בן מיימון) and his Arabic name was موسى بن ميمون بن عبد الله القرطبي الإسرائيلي (Mussa bin Maimun ibn Abdallah al-Kurtubi al-Israili). However, he is most commonly known by his Greek name, Moses Maimonides (Μωησής Μαϊμονίδης), which literally means, "Moses, son of Maimon", like his name in Hebrew and Arabic. Many Jewish works refer to him by the Hebrew acronym of his title and name — Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon — calling him the RaMBaM or the Rambam (רמב"ם).

Contents

View on Noahides

- See Also Maimonides' Law of Noahides

A simple reading of the rules of Maimonides' would indicate that Jews or a Jewish court are obligated in (at the minimum) coercing Noachides to observe their laws. Such is not the only way, however, to interpret Maimonides' statements. Maharatz Chayut in his responsa[Responsa 2.] seems to adopt a formulation of Maimonides ruling that makes this law a mere historical recounting of facts. He states (quoting the Rashbash[ Rabbi Shlomo Ben Shimon Duran, Rashbash 543. ]):

- Sanhedren 56b recounts that the Jews were commanded in ten commandments at Marah[ See "Dinim" Encyclopedia Talmudit 7:396-397 for a discussion of this issue. ]; these ten commandments were the seven laws of Noah, the Sabbath laws, dinim, and respect for one's parents. Why did the Jews need to be commanded again [on the seven Noachide laws] since Jews were already commanded from the time of Adam and Noah...Since we conclude that commandments that were given prior to Sinai to Noachides, and not repeated at Sinai, are obligatory only for Jews, the seven commandments had to be repeated at Sinai to obligate Noachides.[ The general rule is that commandments apparently directed to all recounted in the bible prior to revelation at Sinai are binding only on Jews; commandments recounted twice in the bible, one before revelation and once after are binding on all; see generally Encyclopedia Talmudit, supra note *, at 359-360. ] Based on this Rashbash, the assertion of Maimonides that "Moses, our teacher, only willed Torah and mitzvot to the Jewish people, since it states 'An inheritance to the community of Jacob.'" ... and his assertion that 'Moses our teacher was commanded by God to compel the commandments obligatory to the children of Noah' appear logical. Why was Moses also the messenger to the rest of the world to compel observance of the seven commandments, perhaps they are obligated by Adam or Noach? Rather we see that Moses being commanded at Marah on the seven Noachide commandments, even though Gentiles were already commanded, was done to make Noachides obligated in the mitzvot even now.

Thus, according to Maharatz Chayut, there is no obligation for any specific Jew, in any circumstance to compel observance by a Noachide. Rather Maimonides is merely explaining the jurisprudential basis for the obligation of Noachides to their seven commandments -- absent Moses' re-commandment at Sinai, only Jews would have been obligated in Noachide law. The most that one could claim according to Maharatz Chayut is that perhaps Moses himself was obligated to compel observance of the Noachide laws; Jews currently are not -- apparently neither in the context of a beit din nor in the context of any specific individual. Maharatz Chayut would then limit Maimonides' rule obligating Jews to establish courts and appoint judges to those Noachides who formally accept the obligations of a ger toshav (resident alien) and who live in the Jewish community and who are dependent on it for law and order "lest the world be destroyed".[ Maimonides Malachim 10:11. ] Certainly in the diaspora there are few such communities of Noachides; although if there were, and they could not see fit to enforce the law themselves, a Jew should guide them. Similar claims that Maimonides' rules do not create a practical legal obligation can be found in Aruch Hashulchan,[YD 267:12-13] the writings of Rabbi Yehuda Gershuni,[ Rabbi Yehuda Gershuni (Mishpatai Melucha 2d ed. pages 232-234)] Rabbi Shaul Yisrali[ Amud Yemini 12:1:12.] and Rabbi Menachem Mendel Kasher,[ Torah Shelama 17:220] the author of Torah Shelama, all of whom assert that the opinion of Maimonides itself is to be understood as limited to yemot hamashe'ach (or perhaps less ideally, full Jewish law in Israel).

However, all of these explanations of Maimonides' ruling are difficult and the simple understanding of Maimonides is that (at the least) a person that is capable of forcing compliance, must. Indeed, while Rabbi Karo does appear to limit the application of Maimonides somewhat, he clearly understands Maimonides as requiring compulsion whenever possible, even by an individual.[ Kesef Mishnah Mila 1:6] This is similarly understood to be the opinion of Maimonides by Tzafnach Panaich, in his lengthy discussion on this topic.[ Rabbi Joseph Rosen, Tzafnach Paneach, Maimonides, Milah 1:6] A ruling similar to Maimonides' is found in Chinuch 192, where it states:

- The rule is as follows: In all that the nations are commanded, any time they are under our jurisdiction, it is incumbent upon us to judge them when they violate the commandments.

Biography

Maimonides was born in 1135 in Córdoba, Spain, then under Muslim rule during what some scholars consider to be the end of the golden age of Jewish culture in Spain. Maimonides studied Torah under his father Maimon who had in turn studied under Rabbi Joseph ibn Migash. The Almohades conquered Córdoba in 1148, and offered the Jewish community the choice of conversion to Islam, death, or exile. Maimonides's family, along with most other Jews, chose exile. For the next ten years they moved about in southern Spain, avoiding the conquering Almohades, but eventually settled in Fes in Morocco, where Maimonides acquired most of his secular knowledge, studying at the University of Fes. During this time, he composed his acclaimed commentary on the Mishnah.

Following this sojourn in Morocco, he briefly lived in the Holy Land, spending time in Jerusalem, and finally settled in Fostat, Egypt; where he was doctor of the Grand Vizier Alfadhil and also possibly the doctor of Sultan Saladin of Egypt. In Egypt, he composed most of his oeuvre, including the Mishneh Torah. He died in Fostat, and was buried in Tiberias (today in Israel). His son Avraham, recognized as a great scholar, succeeded him as Nagid (head of the Egyptian Jewish Community), as well as in the office of court physician, at the age of only eighteen. He greatly honored the memory of his father, and throughout his career defended his father's writings against all critics. The office of Nagid was held by the Maimonides family for four successive generations until the end of the 14th century.

He is widely respected in Spain and a statue of him was erected in Córdoba alongside his synagogue, which is no longer functioning as a Jewish house of worship but is open to the public. There is no Jewish community in Córdoba now, but the city is proud of its historical connection to Rambam.

Works and bibliography

Maimonides composed both works of Jewish scholarship, and medical texts. Most of Maimonides' works were written in Arabic. However, the Mishneh Torah was written in Hebrew. His Jewish texts were:

- The Commentary on the Mishna, written in Arabic. This text was one of the first commentaries of its kind; its introductory sections are widely-quoted. See Mishnah Commentaries for details;

- Sefer Hamitzvot ("The Book of Commandments"). See 613 mitzvot for details;

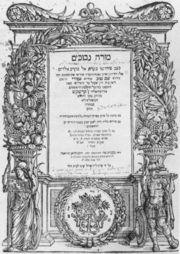

- The Mishneh Torah (also known as " Sefer Yad ha-Chazaka"), a comprehensive code of Jewish law;

- The Guide for the Perplexed, a philosophical work harmonising and differentiating Aristotelian philosophy and Jewish theology;

- Teshuvot, collected correspondence and responsa, including a number of public letters (on resurrection and the after-life, on conversion to other faiths, and Iggereth Teiman - addressed to the oppressed Jewry of Yemen).

Maimonides also wrote a number of medical texts; some of which are still in existence. The best known is his collection of medical aphorisms, titled Fusul Musa in Arabic ("Chapters of Moses", Pirkei Moshe in Hebrew).

Influence

Maimonides was by far the most influential figure in medieval Jewish philosophy. A popular medieval saying that also served as his epitaph states, From Moshe (of the Torah) to Moshe (Maimonides) there was none like Moshe.

Radical Jewish scholars in the centuries that followed can be characterised as "Maimonideans" or "anti-Maimonideans". Moderate scholars were eclectics who largely accepted Maimonides' Aristotelian world-view, but rejected those elements of it which they considered to contradict the religious tradition. Such eclecticism reached its height in the 14th-15th centuries.

The most rigorous medieval critique of Maimonides is Hasdai Crescas' Or Hashem. Crescas bucked the eclectic trend, by demolishing the certainty of the Aristotelian world-view, not only in religious matters, but even in the most basic areas of medieval science (such as physics and geometry). Crescas' critique provoked a number of 15th century scholars to write defenses of Maimonides. A translation of Crescas was produced by Harry Austryn Wolfson of Harvard University, in 1929.

- See also Maimonides School

The 13 principles of faith

See also the main article Jewish principles of faith

In his commentary on the Mishna (tractate Sanhedrin, chapter 10), Maimonides formulates his 13 principles of faith. They described his views on:

- The existence of God

- God's unity

- God's spirituality and incorporeality

- God's eternity

- God alone should be the object of worship

- Revelation through God's prophets

- The preeminence of Moses among the prophets

- God's law given on Mount Sinai

- The immutability of the Torah as God's Law

- God's foreknowledge of human actions

- Reward of good and retribution of evil

- The coming of the Jewish Messiah

- The resurrection of the dead

These principles were controversial when first proposed, evoking criticism by Hasdai Crescas and Joseph Albo, and were effectively ignored by much of the Jewish community for the next few centuries. ("Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought", Menachem Kellner). However, these principles became widely-held; today, Orthodox Judaism holds these beliefs to be obligatory. Two poetic restatements of these principles (Ani Ma'amin and Yigdal) eventually became canonized in the "siddur" (Jewish prayer book).

Halakhic works

See also Mishneh Torah on his influence in halakha

With Mishneh Torah, Maimonides composed a code of Jewish law with the widest-possible scope and depth. The work gathers all the binding laws from the Talmud, and incorporates the positions of the Geonim (post-Talmudic early Medieval scholars, mainly from Mesopotamia). It is a highly-systematised work, and employs a very clear Hebrew, reminiscent of the style of the Mishna.

While Mishneh Torah is now considered the fore-runner of the Arbaah Turim and the Shulkhan Arukh (two later codes), it met initially with much opposition. There were two main reasons for this opposition. Firstly, Maimonides had refrained from adding references to his work for the sake of brevity. Secondly, in the introduction, he gave the impression of wanting to "cut out" study of the Talmud, to arrive at a conclusion in Jewish law. His most forceful opponents were the rabbis of the Provence (Southern France), and a running critique by Rabbi Abraham ibn Daud (Raavad III) is printed in virtually all editions of Mishneh Torah.

Philosophy

Through the Guide for the Perplexed and the philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishna, Maimonides exerted an important influence on the Scholastic philosophers, especially on Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, and Duns Scotus. He was himself a Jewish Scholastic. Educated more by reading the works of Arab Muslim philosophers than by personal contact with Arabian teachers, he acquired an intimate acquaintance not only with Arab Muslim philosophy, but with the doctrines of Aristotle. Maimonides strove to reconcile Aristotelian philosophy and science, with the teachings of the Torah.

Negative theology

The principle which inspired his philosophical activity was identical with the fundamental tenet of Scholasticism: there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed, and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy. Maimonides primarily relied upon the science of Aristotle and the philosophies of the Talmud and Aristotle, commonly finding basis in the former for the latter. In some important points, however, he departed from the teaching of Aristotle; for instance, he rejected the Aristotelian doctrine that God's provident care extends only to humanity, and not to the individual.

Maimonides was led by his admiration for the neo-Platonic commentators to maintain many doctrines which the Scholastics could not accept. For instance, Maimonides was an adherent of "negative theology" (also known as "Apophatic theology".) In this theology, one attempts to describe God through negative attributes. For instance, one should not say that God exists in the usual sense of the term; all we can safely say is that God is not non-existent. We should not say that "God is wise"; but we can say that "God is not ignorant", i.e. in some way, God has some properties of knowledge. We should not say that "God is One", but we can state that "there is no multiplicity in God's being". In brief, the attempt is to gain and express knowledge of God by describing what God is not; rather than by describing what God "is".

The Scholastics agreed with him that no predicate is adequate to express the nature of God; but they did not go so far as to say that no term can be applied to God in the affirmative sense. They admitted that while "eternal", "omnipotent", etc., as we apply them to God, are inadequate, at the same time we may say "God is eternal" etc., and need not stop, as Moses did, with the negative "God is not not-eternal", etc. In essence what Maimonides wanted to express is that when people give God anthropomorphic qualities they do not do justice to His greatness.

Prophecy

He agrees with "the philosophers" in teaching that, man's intelligence being one in the series of intelligences emanating from God, the prophet must, by study and meditation, lift himself up to the degree of perfection required in the prophetic state. But here, he invokes the authority of "the Law", which teaches that, after that perfection is reached, there is required the "free act of God", before the man actually becomes a prophet.

The problem of evil

Maimonides wrote on theodicy, the attempt to reconcile the existence of evil, with the premise that an omnipotent and good God exists. He follows the neo-Platonists in laying stress on matter as the source of all evil and imperfection.

Astrology

Maimonides answered an inquiry concerning astrology, addressed to him from Marseille. He responded that man should believe only what can be supported either by rational proof, by the evidence of the senses, or by trustworthy authority. He affirms that he had studied astrology, and that it does not deserve to be described as a science. The supposition that the fate of a man could be dependent upon the constellations is ridiculed by him; he argues that such a theory would rob life of purpose, and would make man a slave of destiny. (See also fatalism, predestination.)

True beliefs versus necessary beliefs

In "Guide for the Perplexed" Book III, Chapter 28, Maimonides explicitly draws a distinction between "true beliefs", which were beliefs about God which produced intellectual perfection, and "necessary beliefs", which were conducive to improving social order. Maimonides places anthropomorphic statements about God in the latter class. He uses as an example, the notion that God becomes "angry" with people who do wrong. In the view of Maimonides, God does not actually become angry with people; but it is important for them to believe God does, so that they desist from sinning.

Resurrection, acquired immortality, and the afterlife

Maimonides distinguishes two kinds of intelligence in man, the one material in the sense of being dependent on, and influenced by, the body, and the other immaterial, that is, independent of the bodily organism. The latter is a direct emanation from the universal active intellect; this is his interpretation of the noûs poietikós of Aristotelian philosophy. It is acquired as the result of the efforts of the soul to attain a correct knowledge of the absolute, pure intelligence of God.

The knowledge of God is a form of knowledge which develops in us the immaterial intelligence, and thus confers on man an immaterial, spiritual nature. This confers on the soul that perfection in which human happiness consists, and endows the soul with immortality. One who has attained a correct knowledge of God has reached a condition of existence which renders him immune from all the accidents of fortune, from all the allurements of sin, and even from death itself. Man, therefore is in a position not only to work out his own salvation and immortality.

The resemblance between this doctrine and Spinoza's doctrine of immortality is so striking as to warrant the hypothesis that there is a causal dependence of the later on the earlier doctrine. The differences between the two Jewish thinkers are, however, as remarkable as the resemblance. While Spinoza teaches that the way to attain the knowledge which confers immortality is the progress from sense-knowledge through scientific knowledge to philosophical intuition of all things sub specie æternitatis, Maimonides holds that the road to perfection and immortality is the path of duty as described in the Torah and the rabbinic understanding of the oral law.

Religious Jews not only believed in immortality in some spiritual sense, but most believed that there would at some point in the future be a messianic era, and a resurrection of the dead. This is the subject of Jewish eschatology. Maimonides wrote much on this topic, but in most cases he wrote about the immortality of the soul for people of perfected intellect; his writings were usually not about the resurrection of dead bodies. This prompted hostile criticism from the rabbis of his day, and sparked a controversy over his true views.

Rabbinic works usually refer to this afterlife as "Olam Haba" (the World to Come). Some rabbinic works use this phrase to refer to a messianic era, an era of history right here on Earth; in other rabbinic works this phrase refers to a purely spiritual realm. It was during Maimonides's lifetime that this lack of agreement flared into a full blown controversy, with Maimonides charged as a heretic by some Jewish leaders.

Some Jews at this time taught that Judaism did not require a belief in the physical resurrection of the dead, as the afterlife would be a purely spiritual realm. They used Maimonides' works on this subject to back up their position. In return, their opponents claimed that this was outright heresy; for them the afterlife was right here on Earth, where God would raise dead bodies from the grave so that the resurrected could live eternally. Maimonides was brought into this dispute by both sides, as the first group stated that his writings agreed with them, and the second group portrayed him as a heretic for writing that the afterlife is for the immaterial spirit alone. Eventually, Maimonides felt pressured to write a treatise on the subject, the "Ma'amar Tehiyyat Hametim" "The Treatise on Resurrection."

Chapter two of the treatise on resurrection refers to those who believe that the world to come involves physically resurrected bodies. Maimonides refers to one with such beliefs as being an "utter fool" whose belief is "folly".

- If one of the multitude refuses to believe [that angels are incorporeal] and prefers to believe that angels have bodies and even that they eat, since it is written (Genesis 18:8) 'they ate', or that those who exist in the World to Come will also have bodies—we won't hold it against him or consider him a heretic, and we will not distance ourselves from him. May there not be many who profess this folly, and let us hope that he will go farther than this in his folly and believe that the Creator is corporeal.

However, Maimonides also writes that those who claimed that he altogether believed the verses of the Hebrew Bible referring to the resurrection were only allegorical were spreading falsehoods and "revolting" statements. Maimonides asserts that belief in resurrection is a fundamental truth of Judaism about which there is no disagreement, and that it is not permissible for a Jew to support anyone who believes differently. He cites Daniel 12:2 and 12:13 as definitive proofs of physical resurrection of the dead when they state "many of them that sleep in the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence" and "But you, go your way till the end; for you shall rest, and will arise to your inheritance at the end of the days."

While these two positions may be seen as in contradiction (non-corporeal eternal life, versus a bodily resurrection), Maimonides resolves them with a then unique solution: Maimonides believed that the resurrection was not permanent or general. In his view, God never violates the laws of nature. Rather, divine interaction is by way of angels, which Maimonides holds to be metaphors for the laws of nature, the principles by which the physical universe operates, or Platonic eternal forms. Thus, if a unique event actually occurs, even it is perceived as a miracle, it is not a violation of the world's order (Commentary on the Mishna, Avot 5:6.)

In this view, any dead who are resurrected must eventually die again. In his discussion of the 13 principles of faith, the first five deal with knowledge of God, the next four deal with prophecy and the Torah, while the last four deal with reward, punishment and the ultimate redemption. In this discussion Maimonides says nothing of a universal resurrection. All he says it is that whatever resurrection does take place, it will occur at an indeterminate time before the world to come, which he repeatedly states will be purely spiritual.

He writes "It appears to us on the basis of these verses (Daniel 12:2,13) that those people who will return to those bodies will eat, drink, copulate, beget, and die after a very long life, like the lives of those who will live in the Days of the Messiah." Maimonides thus disassociated the resurrection of the dead from both the World to Come and the Messianic era.

In his time, many Jews believed that the physical resurrection was identical to the world to come; thus denial of a permanent and universal resurrection was considered tantamount to denying the words of the Talmudic sages. However, instead of denying the resurrection, or maintaining the current dogma, Maimonides posited a third way: That resurrection had nothing to do with the messianic era (here in this world) nor to do with Olam Haba (the purely spiritual afterlife). Rather, he considered resurrection to be a miracle that the book of Daniel predicted; thus at some point in time we could expect some instances of resurrection to occur temporarily, which would have no place in the final eternal life of the righteous.

Maimonides and the Modern

Maimonides remains the most widely debated and controversial Jewish thinker among modern scholars. He has been adopted as a symbol and an intellectual hero by almost all major movements in modern Judaism, and has proven immensely important to modern Jewish philosophers such as Leo Strauss. Maimonides's importance to diverse systems of thought lies in the philosopher's embrace of paradoxical and often contradictory ideas. The Reform movement, for instance, pointed out Maimonides's argument that Jewish ritual has developed over time as justification for its proposed changes to Jewish tradition. Orthodoxy, on the other hand, has pointed to the Maimonidean argument that the Oral Law (Halacha) and the Principles of Faith are inviolate and must be scrupulously observed even if they are not fully understood. Maimonides's reconciliation of the philosophical and the traditional has given his legacy an extremely diverse and dynamic quality. He is one of the few figures in Jewish history who is universally embraced by all strains of modern Judaism. Jewish historian Yosef Yerushalmi has noted that every generation creates the Maimonides it needs or desires.

One of the major issues regarding Maimonides' work is the obscure nature of Guide for the Perplexed. Leo Strauss, who held that Maimonides was the most important philosopher who ever lived, has theorized that Maimonides deliberately intended his book to have two meanings. The first, obvious meaning, was intended for his average readers. The second, hidden meaning, was intended for his elite readers who would understand it due to their intellectual sophistication. Strauss believed that Maimonides telegraphed his real meaning by using codes, numerological indications, and deliberate contradictions within the text. Strauss's writings remain controversial, although he is now accepted as one of the most important modern scholars of Maimonides's philosophy.

Modern scholars tend to fall into two camps: those who believe that Maimonides was attempting a synthesis between Judaism and Aristotelian philosophy, and those who hold that Maimonides was, in fact, a secret Aristotelian who saw Jewish tradition as an allegorical system which was intended to maintain the Jewish community, but was not philosophically accurate. This debate appears unlikely to ever be resolved, since it is based in differing exegetical readings of Maimonides's obscure and difficult philosophical works.

References

- Marvin Fox Interpreting Maimonides, Univ. of Chicago Press 1990.

- Julius Guttman, Philosophies of Judaism Translated by David Silverman, JPS, 1964

- Maimonides' Principles: The Fundamentals of Jewish Faith, in "The Aryeh Kaplan Anthology, Volume I", Mesorah Publications 1994

- Dogma in Medieval Jewish Thought, Menachem Kellner, Oxford University press, 1986

- Maimonides Thirteen Principles: The Last Word in Jewish Theology? Marc. B. Shapiro, The Torah U-Maddah Journal, Vol. 4, 1993, Yeshiva University

- A History of Jewish Philosophy, Isaac Husik, Dover Publications, Inc., 2002. Originally published in 1941 by the Jewish Publication of America, Philadelphia, pp. 236-311

- Persecution and the Art of Writing, Leo Strauss, University of Chicago Press, 1988 reprint

- "How to Begin to Study the Guide", Leo Strauss, from The Guide of the Perplexed, Vol. 1, Maimonides, translated from the Arabic by Shlomo Pines, University of Chicago Press, 1974

External links

- A brief Biography of Maimonides

- Maimonides/Rambam from the Jewish Virtual Library

- Maimonidean controversy

- Writings of Maimonides (Manuscripts and Early Print Editions)

- Maimonides Page: links to online resources

- The Foundations of Jewish Belief

- Rambam's introduction to the Mishnah Torah (English translation)

- Rambam's introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah (Hebrew Fulltext)

- The Guide For the Perplexed by Moses Maimonides translated into English by Michael Friedländer

- Maimonides Mishneh (or Mishnah) Torah or Rambam - the codified laws compiled by Maimonides

- Oath and Prayer of Maimonides, as a choice instead of the Hippocratic Oath in medical profession.